Single-sex schools: cui bono?

27th January 2016 by Timo Hannay [link]

This item has also been cross-posted on the Good Schools Guide blog.

Single-sex schools have been in the news again recently, with some commentators claiming that they are counterproductive and various others defending them. Given the release last week of full 2015 GCSE results, I thought this a useful opportunity to look at the numbers, and to use them to try and answer a few pertinent questions: Do single-sex schools really do better academically? Is their gender mix the only thing that makes them different from mixed schools? And does single-sex education itself have any positive effects on pupil performance? The answers, it turns out, are yes, no and maybe if you're a girl. To find out more, read on.

First, a disclosure. One of my three children attends a girls' grammar school. (The other two attend a mixed-sex primary school.) I had an exclusively co-educational schooling and, all other things being equal, tend to favour inclusive approaches to education. But I don't have strong feelings either way regarding single-sex schools and and my purpose here is solely to explore the available data, not to make a case for or against any particular approach.

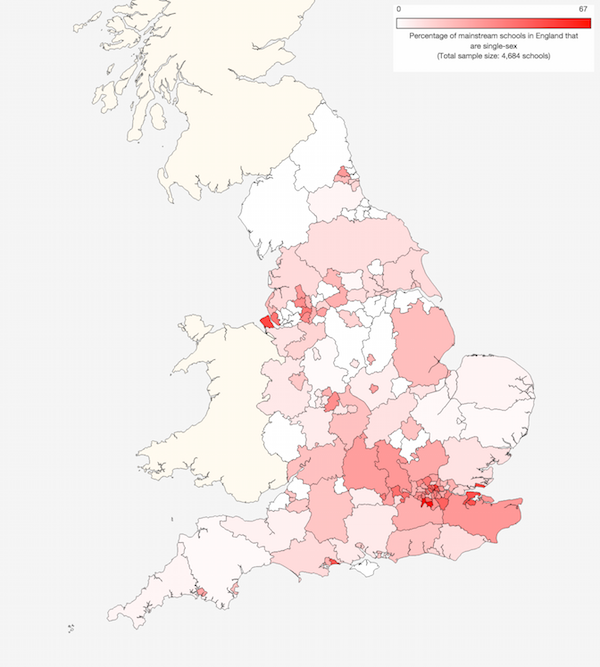

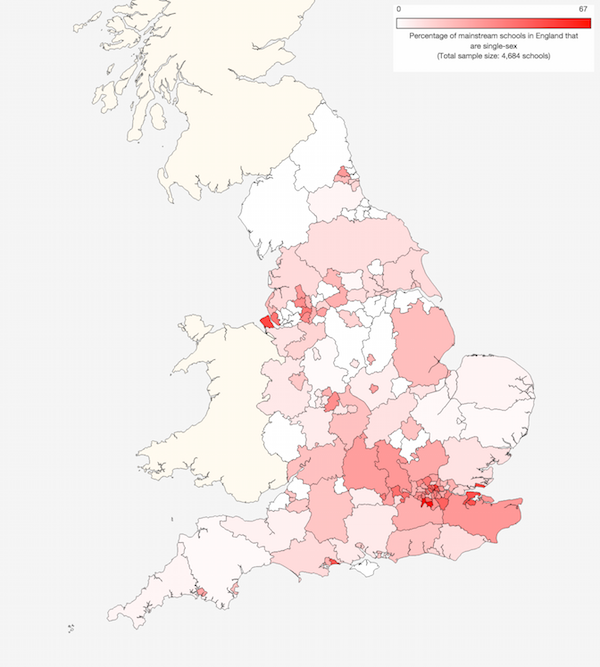

According to data from the Department for Education (DfE), there are 726 mainstream single-sex secondary schools in England, representing just over 15% of all secondary schools1. One of the most striking characteristics of these schools is that they are very unevenly distributed, with particular hotspots in London and the Thames Estuary, Liverpool and (intriguingly) Bournemouth, as well as, to a lesser extent, other major cities (see Map 1 below; click on it to go to an interactive version):

Map 1: Distribution of single-sex secondary schools in England

Girls' schools are more common (58% of the total) than boys' schools (42%), but at the national level there's relatively little difference in the distributions of these two groups.

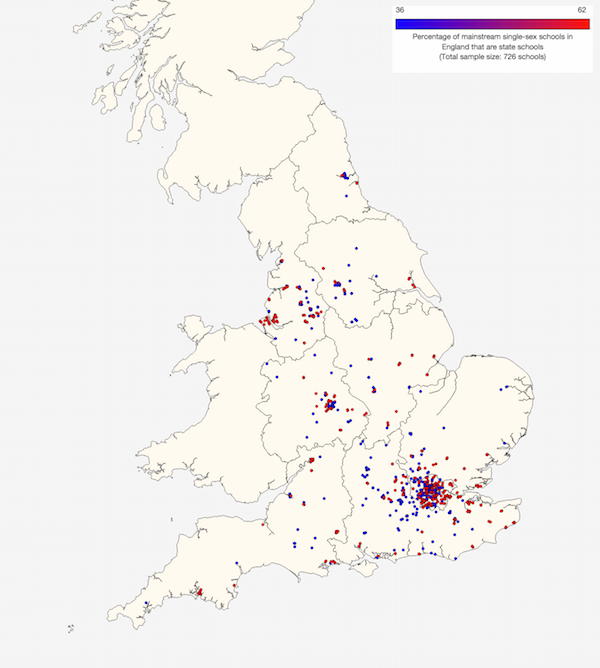

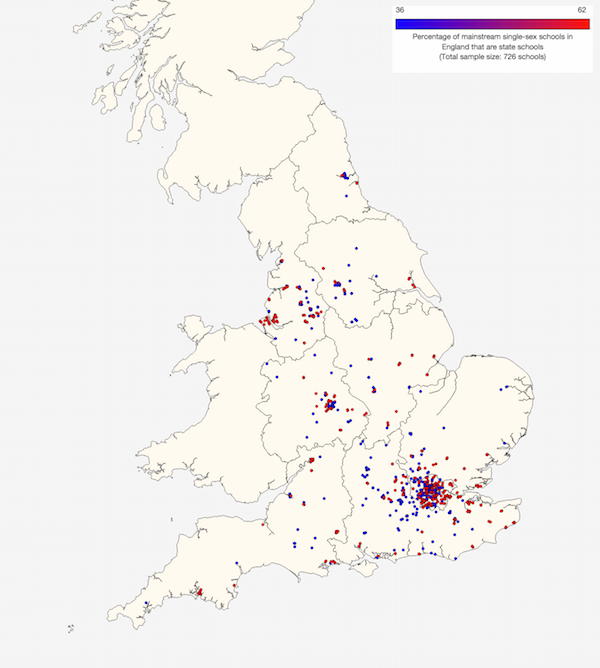

Independent (ie, private) schools are heavily over-represented, comprising 48% of single-sex secondary schools compared to only 27% of all secondary schools. The following map shows single-sex state schools in red and single-sex private schools in blue:

Map 2: Locations of state and private single-sex secondary schools in England

In addition to the clustering of such schools around places like London and Liverpool, different patterns are displayed by the state schools (which predominate, for example, in Merseyside and to the east of London) and private schools (which are more numerous to the north of Manchester and to the west of London). Presumably this is driven in large part by the relative wealth of these different areas.

The ratio of single-sex state schools to single-sex private schools therefore varies markedly across the country and is different for boys' schools and girls' schools.

The rest of this analysis will concentrate on single-sex state schools. This is for two reasons:

- Taxpayer-funded single-sex schools are a particularly interesting social phenomenon. As we have seen, they are controversial and in recent decades have declined across the world, but they persist in some countries, not least Britain. (In these aspects they are not dissimilar to state-funded faith schools, and as we shall see there is in a fact a degree of overlap between the two groups.)

- The DfE gathers and makes available a wide range of data about these and other state schools that simply isn't available for private schools. This makes them much more amenable to analysis.

It's worth acknowledging that so far we've been talking solely about schools in England. In fact this is not unreasonable since British single-sex state schools are overwhelmingly an English phenomenon: there are only four such schools in Wales2 and one in Scotland3. In addition, they are almost exclusively urban: there is only one rural single-sex state school in the whole country (a very unusual state-funded boarding school for boys).

As well as focusing on England, we're also looking specifically at secondary schools. Again, the nature of single-sex education supports such an approach. There are only seven single-sex state primary schools in England4, five of which are Jewish faith schools. Sixth-forms, too, are overwhelmingly co-educational, even among colleges that are affiliated with single-sex secondary schools.

State schools of the nation

There are 378 mainstream single-sex state secondary schools in England, 161 for boys and 217 for girls. (These numbers, and the analysis below, omit three recently opened Muslim faith schools for which there is currently insufficient data to do any meaningful analysis5.)

I know what you're wondering, so let's dive straight in and look at how well these schools do at GCSEs (hover your mouse over each bar to see the exact values):

Figure 1: Pupils obtaining at least five good GCSEs (2015)

Well that seems pretty clear. Across England just over 57% of pupils get five good GCSEs. Most of them are at mixed schools, which collectively come in slightly below the national average. In contrast, the small minority of single-sex schools do much better – 20 percentage points better – with girls' schools performing at a slightly higher level than boys' schools, at least on this particular measure.

But not so fast. Single-sex schools might be different from mixed schools not only in their gender balance but in other ways too, and those other factors might be causing some or all of this difference. If so then how are single-sex schools different?

Let me count the ways

Perhaps most important of all, single-sex schools are much more likely to be grammar schools (ie, to select pupils based on academic ability). Almost a third – 120 out of 378 – of single-sex state secondary schools are grammar schools. Conversely, nearly three-quarters of grammar schools are single-sex. As a result, the average Key Stage 2 point score (a measure of academic attainment at age 11) of pupils entering single-sex schools is higher (29.3) than that of pupils entering mixed schools (27.3). Even more strikingly, pupils categorised as having high prior attainment make up a much larger proportion in single-sex schools than in mixed schools, and the reverse is true for those with medium or low prior attainment (see Figure 2):

Figure 2: Pupil characteristics (2015*)

This surely has a lot to do with their academic success, but there are other differences too. For example, single-sex schools have higher proportions of South Asian and black pupils, among other less common ethnic minorities, and therefore fewer white pupils than mixed schools do. (Note the different scales for each ethnic group: white pupils still account for the majority even in single-sex schools.) Such a variegated ethnic profile is perhaps to be expected given the urban locations of single-sex schools. Also consistent with this picture are the higher proportions of pupils for whom English is an additional language (EAL). I used to naively assume this to be an educational disadvantage, but have since learned that it is often seen among educationalists as a positive indicator because it tends to correlate with immigrant ethnic groups that take education very seriously.

Despite their urban locations and high proportions of ethnic-minority pupils, however, single-sex schools tend to have lower proportions of children who are eligible for free school meals (FSM) or the Deprivation Pupil Premium (DPP), both signs of poverty. They also have lower numbers of pupils with special educational needs (SEN; defined as those with a SEN statement or on School Action Plus).

In contrast, there's no significant difference in average school size, with mixed schools serving a mean of 945 pupils compared to 948 for single-sex schools. Pupil:teacher ratios are also essentially the same for both groups (in the range 15.0-15.1). Single-sex schools are more likely to be associated with a religious faith (29% versus 17% of mixed schools). Particularly prominent are Roman Catholic schools (17% of single-sex schools but only 8% of mixed schools) and Muslim schools (10 single-sex schools, corresponding to 3%, but only a single mixed school among more than 3,000). A clear majority (84%) of mixed schools are in urban locations; as already mentioned this is true of all but one single-sex school.

Let's now look at teachers. There's no significant difference in the overall proportions of male teachers (just under 38% in mixed schools versus just over 37% in single-sex schools), but this hides a big underlying difference between boys' schools, where nearly 55% of teachers are men, and girls' schools, where only 24% are. This trend is even more extreme among teaching assistants, though the absolute proportions of men are much lower in that case (see Figure 3):

Figure 3: Teacher characteristics (2014)

Teachers at single-sex schools are slightly older (23% are over 50) than those at mixed schools (where 19% are over 50) and perhaps as a result of this earn slightly more (a mean of £39,500 versus £38,100). Single-sex schools also lose fewer days through staff sickness (298 days annually versus 349 days for mixed schools). I have no idea why this should be (are single-sex schools less stressful for teachers?), but the effect is present in all the years for which comparable data are available (2011-14), and boys' schools tend to lose fewer days than girls' schools (273 versus 316). It's perhaps worth pointing out that this teacher data is older than most of the other information presented here (from 2014 rather than 2015) and is also based on smaller sample sizes, so may be worth taking with a small pinch of salt.

Given all this – particularly the findings that single-sex schools tend to cater disproportionately to relatively able, wealthy and ethnically diverse city kids – it's not unreasonable to think that their higher performance is caused by a combination of factors in addition to (or perhaps instead of) their single-sex status. But how to test this?

Creating a control

The approach we have chosen here is to create a subset of mixed schools that are in other ways as similar as possible to the group of single-sex schools, and then to compare the performance of these two groups. By doing this we can control for certain factors that might be obscuring the effects (if any) of single-sex education itself.

This subset of mixed schools was created by taking each single-sex school in turn and finding the mixed school that was most similar to it on the basis of the following criteria:

- Whether or not school admissions are based on academic ability.

- Pupils' prior academic attainment levels and scores.

- The proportion of pupils for whom English is an additional language (EAL).

- The proportion of disadvantaged pupils, as measured by their eligibility for free school meals (FSM) and the Deprivation Pupil Premium (DPP).

- The proportion of pupils who have special educational needs (SEN).

The result is a group of 378 mixed schools that are unusually similar in these other respects to the group of single-sex schools. Note that these are not 378 different mixed schools (the actual number is 259) because in some cases a particular mixed school turned out to be the closest match for more than one single-sex school. This approach has the potential disadvantage of amplifying any statistical anomalies in the schools represented more than once. But the alternative would have been to include mixed schools that really aren't very similar to those in the single-sex group, particularly in their admissions policies, which would have defeated the object of the exercise. On average, each mixed school in this group is represented 1.45 times, and the vast majority are represented just once, but several are represented anywhere between 2 and 6 times, and one school (Chislehurst and Sidcup Grammar School) is represented no less than 10 times – thus gaining the unusual distinction of being the establishment in England that is most like a single-sex school without actually being a single-sex school.

Figure 4 below shows the same pupil attributes as those in Figure 2 above, but this time with data for the new group of 'Similar mixed schools' added:

Figure 4: Pupil characteristics (2015*)

As you can see, this new subset of mixed schools has proportions of pupils with high, medium and low prior attainment, as well as proportions of EAL, FSM, DPP and SEN students, that are very similar to those in the single-sex group. This is unsurprising since these are the main criteria by which they were chosen. For the same reason, pupils in this group show a very similar average Key Stage 2 points score (29.2) to those in the mixed schools (29.3), and it contains an identical proportion (32%) of selective schools. Interestingly, it also matches reasonably well in terms of ethnic balance (South Asian, black and white/other) even though no explicit matching was done on this basis.

Truly eagle-eyed readers6 may notice that some of the numbers for the single-sex schools group used in Figure 4 are slightly different to those used in Figure 2. This is because not every data field is available for every school and in Figure 4 we have taken the extra precaution of including a single-sex school only if data for its corresponding mixed school is also available (and vice versa). This allows us to make sure we're comparing like with like, though in practice it makes little difference to the numbers.

There are some differences between the group of single-sex schools and the subset of similar mixed schools. The most significant is that the mixed schools are larger (catering for an average of 1,117 pupils compared to 948). They are also slightly less likely to be religious (22% versus 29%) or urban (92% versus almost 100%). In addition, they aren't quite as South-Eastern as single-sex schools. One way to think about this is to consider the mean latitude and longitude of the schools in each group. Defined in this way, the average location of all mainstream secondary schools in England is between Coventry and Leicester, and the group of all mixed schools come out in almost exactly the same place. The average location of all single-sex state secondary schools, however, is just south-west of Milton Keynes. The subset of 'similar' mixed schools come out in between these two points, just south of Northampton.

Exam results

With these things in mind, let's see how this new group performs at GCSEs:

Figure 5: GCSE results (2015)

For overall GCSE attainment, the gap between single-sex schools and mixed schools closes dramatically when we control for these other factors – from 20 percentage points to less than 3 percentage points. Furthermore, it seems slightly higher for girls (just over 3 points) than for boys (just over 2 points), though such a small difference could be mere statistical noise. A proportionally larger effect can be seen for pupils, especially girls, with low prior attainment, though the absolute percentages of pupils concerned are relatively small. For pupils with medium and high levels of prior attainment, the differences are smaller, and for boys they are virtually absent. A slightly bigger absolute difference is seen for disadvantaged pupils7. For non-disadvantaged pupils, the effect is again bigger for girls than for boys.

Similar patterns can seen when looking at more specific measures of progress in English and maths, with the relatively modest differences between mixed and 'similar' single-sex schools being caused mainly by differences among girls, pupils with low prior attainment (see English and maths) and disadvantaged pupils (see English and maths).

Finally, let's look at the DfE's own value-added measure for GCSEs, which takes into account pupils' prior attainment. The raw numbers are typically around 1,000, with relatively small variations above or below this. In order to better see the differences, the numbers presented in Figure 6 below show the amount by which the value-added score is above (positive numbers) or below (negative numbers) this middle value of 1,000. First a look at the overall GCSE value-added measure:

Figure 6: GCSE Value-Added Measure

Here the picture seems even clearer, with single-sex schools showing significant benefits over mixed schools (though nowhere near as big as they would be without controlling for other factors). However, in every group – whether among pupils who showed high, medium or low prior attainment, and whether they are disadvantaged or not – the effects for girls are much larger and those for boys appear to be absent.

Note that these variations in the value-added score of a few tens of units either way may look modest compared to the median value of 1,000 but this is not really the case because no schools have scores anywhere near zero. In the 2015 data, any value below 919 would put a school in the lowest 10% in England, and any value above 1049 would put it in the top 10%. In this context, the variations we see here are certainly material.

The overall picture that emerges is one in which single-sex secondary schooling for girls does seem to have some benefits, at least when it comes to these particular measures of GCSE performance. Though it's less clear cut, the same may also be true for poor and/or underachieving pupils – ironically the target groups that single-sex schools tend to avoid. On the other hand, if you've done alright at primary school, come from a reasonably well-off family, and particularly if you're a boy, then going to a single-sex secondary school is unlikely on its own to improve your grades.

These results seem broadly consistent with those of previous studies. But even for girls, they don't necessarily mean that single-sex schooling itself has a positive impact. There may be influences from factors – such as teacher gender or religiosity – that we couldn't fully allow for here. And any number of other unmeasured variables, such as parental factors, might correlate with single-sex schools and also exert an influence. But this analysis does at least provide evidence that pupil characteristics such as academic ability and affluence, whilst apparently responsible for most of the differences in attainment between single-sex and mixed schools, don't quite explain them all. It also raises the interesting question of why girls (perhaps among other groups) seem to benefit more than boys from single-sex schooling – and what, if anything, the majority of mixed schools might be able to learn from this.

[Update added 29/1/16: Following a question from a reader this morning, I'd like to clarify one important thing about interpretation of the valued-added data in Figure 6. It's possible that girls as a whole show more value-added at GCSE than boys. If so then some of the difference we're currently attributing to the single-sex education of girls should in fact be attributed to the single-sex education of boys. (And if the difference between boys and girls at mixed schools is the same as the difference between all-boys and all-girls schools then that would imply no benefits to single-sex education in either boys or girls, at least on this measure.) Unfortunately, as far as we can tell, the data required to answer this question isn't publicly available, but we have requested it. If we're successful and there are any interesting results then we will of course share them. In the meantime, I think the best way to think about this is that available data indicate a benefit for girls while offering little evidence for a similar benefit for boys. However, absence of evidence is not the same as evidence of absence, and further data should help to clarify this. That would still leave other potential confounding factors, both measured and unmeasured – as mentioned in the paragraph above – but that's the nature of all statistical analyses.]

Of course, none of this addresses any effects beyond the narrow confines of GCSE attainment, including such important but notoriously elusive factors as happiness, self-confidence or sociability. Sadly the data in such areas is thin.

So the debate will go on (though if it does so in a slightly better informed manner as a result of this post then it will have served its purpose). And many parents will go on choosing single-sex schools for their children irrespective of whether or not such an education makes a difference on its own. This is for the very understandable reason that, at least in this country, it correlates with other desirable characteristics and therefore acts as a not unreasonable proxy for a good school. If so then this is one aspect of single-sex schooling that I would like to see decline: reducing reliance on indirect indicators in favour of a better understanding of educational characteristics we actually care about is one of the most important aims of SchoolDash.

Footnotes: