Are University Technical Colleges the answer?

27th October 2016 by Timo Hannay [link]

Nicky Morgan, the former Secretary of State for Education, has made no secret of her opposition to the new government's plans to expand the number of grammar schools (ie, selective secondary schools) in England. Yet if this is to happen, she opined in a recent piece for Prospect, then it will be all the more important to support the University Technical College (UTC) programme too. But what are UTCs, what purpose do they serve and what, if anything, have they achieved to date? We've been looking at their exam performance – important even in a vocational context – to assess whether, as a group, UTCs are doing better or worse than other kinds of school.

Decoding the alphabet soup

UTCs are newly created state secondary schools for students aged 14-19 that specialise in providing a technically oriented education. They are academies, which means that they sit outside local authority control and are funded directly from Whitehall. Each is sponsored by a university (and sometimes also partnering charities or companies) that helps to set the curriculum, appoint governors and develop teaching staff. The first one, The JCB Academy, opened in 2010 and there are now 48, most of them founded in the last three years. (You can read more about UTCs here and here.) They are currently located disproportionately in the North West and South East (including London and the East of England). There is only one UTC in the North East with another due to open there next year. A map of their current and planned locations can be found on the website of the Baker Dearing Educational Trust, which promotes and supports UTCs.

UTCs are not to be confused with City Technology Colleges (CTCs), which were launched in the late 1980s. These were also newly established secondary schools with a technical and practical focus, but unlike UTCs they were supported principally by businesses. Only 15 CTCs were ever created and all but three have now converted to ordinary academy status.

Another related group is Studio Schools. These, too, are a new class of standalone secondary schools created under the Academies programme and, like UTCs, serve students aged between 14 and 19. They have a strong vocational bent and forge close links with business. But they are generally smaller than UTCs, with an upper limit of 300 students. There are currently 36 Studio Schools across England.

Subject choice

First let's look at which subjects are studied by students at UTCs compared to those at other types of secondary school. Table 1 shows the proportions of GCSE and equivalent exam entries accounted for by the 20 most popular subjects in 2015 (the most recent year for which detailed statistics are available). It also show how their proportions differ from those at UTCs.

Table 1: Most popular GCSE and equivalent exam subjects at non-UTC state schools in England (2015)

| Subject | Number of entries | Proportion (%) | Difference with UTCs |

|---|

| GCSE Mathematics | 524,948 | 10.7 | -2.4 |

| GCSE English Literature | 380,025 | 7.8 | +0.6 |

| GCSE Science | 366,602 | 7.5 | -1.0 |

| GCSE Additional Science | 303,547 | 6.2 | -1.5 |

| GCSE English Language | 289,211 | 5.9 | +0.9 |

| GCSE Religious Studies | 251,900 | 5.1 | +4.1 |

| GCSE History | 214,864 | 4.4 | +3.1 |

| GCSE Geography | 197,715 | 4.0 | +1.1 |

| CIC English Language | 177,952 | 3.6 | -1.6 |

| GCSE French | 142,307 | 2.9 | +2.6 |

| GCSE Biology | 120,903 | 2.5 | -1.2 |

| GCSE Chemistry | 117,347 | 2.4 | -1.8 |

| GCSE Physics | 116,328 | 2.4 | -1.9 |

| GCSE Physical Education | 102,927 | 2.1 | +1.4 |

| GCSE ICT | 91,694 | 1.9 | +1.0 |

| GCSE Spanish | 80,914 | 1.7 | +0.8 |

| BTEC Applied Sciences | 80,898 | 1.7 | +1.2 |

| GCSE Art & Design | 79,451 | 1.6 | +0.8 |

| GCSE Business Studies | 69,053 | 1.4 | +1.0 |

| GCSE Drama & Theatre Studies | 67,236 | 1.4 | +0.9 |

The corresponding list for UTCs is shown in Table 2. Note that because UTCs are so new, only 13 of the 48 are represented in 2015 these. Nevertheless, it seems clear by comparison with Table 1 that, with the exception of various ubiquitous English subjects, scientific and technical subjects predominate while those in the humanities and modern languages are mostly demoted or absent altogether. (Interestingly, however, German is relatively popular.) We also see vocational qualifications such as Principal Learning and BTECs making an appearance, though GCSEs still predominate.

Table 2: Most popular GCSE and equivalent exam subjects at UTCs (2015)

| Subject | Number of entries | Proportion (%) | Difference with non-UTCs |

|---|

| GCSE Mathematics | 1,128 | 13.1 | +2.4 |

| GCSE Science | 729 | 8.5 | +1.0 |

| GCSE Additional Science | 661 | 7.7 | +1.5 |

| GCSE English Literature | 618 | 7.2 | -0.6 |

| CIC English Language | 448 | 5.2 | +1.6 |

| GCSE English Language | 431 | 5.0 | -0.9 |

| GCSE Physics | 367 | 4.3 | +1.9 |

| GCSE Chemistry | 365 | 4.2 | +1.8 |

| GCSE D&T Product Design | 333 | 3.9 | +3.1 |

| GCSE Biology | 321 | 3.7 | +1.2 |

| Principal Learning Engineering | 304 | 3.5 | +3.5 |

| GCSE Geography | 255 | 3.0 | -1.1 |

| CNC Computer Appreciation | 220 | 2.6 | +1.3 |

| GCSE English Language & Literature | 191 | 2.2 | +1.0 |

| GCSE German | 148 | 1.7 | +0.7 |

| BTEC Engineering Studies | 140 | 1.6 | +1.5 |

| CIC English Literature | 140 | 1.6 | +1.2 |

| GCSE Environmental Science | 122 | 1.4 | +1.4 |

| GCSE Media Studies | 121 | 1.4 | +0.4 |

| GCSE History | 112 | 1.3 | -3.1 |

The picture at A-Level is even more mixed. Table 3 shows the top 10 most popular subjects in non-UTC schools.

Table 3: Most popular A-Level and equivalent exam subjects at non-UTC state schools in England (2015)

| Subject | Number of entries | Proportion (%) | Difference with UTCs |

|---|

| A-Level Mathematics | 55,665 | 8.9 | -2.4 |

| A-Level Biology | 37,722 | 6.0 | +2.9 |

| A-Level History | 34,979 | 5.6 | +5.6 |

| A-Level Psychology | 33,830 | 5.4 | +4.2 |

| A-Level English Literature | 33,168 | 5.3 | +4.2 |

| A-Level Chemistry | 32,425 | 5.2 | +1.6 |

| A-Level Geography | 25,030 | 4.0 | +3.3 |

| A-Level Physics | 23,092 | 3.7 | -5.1 |

| A-Level Economics | 19,201 | 3.1 | +3.0 |

| A-Level Sociology | 16,646 | 2.7 | +2.5 |

As you might expect, these are all standard A-Level subjects. In contrast, the corresponding top 10 list for UTCs, shown in Table 4, contains a majority of vocational qualifications, especially BTECs.

Table 4: Most popular A-Level and equivalent exam subjects at UTCs (2015)

| Subject | Number of entries | Proportion (%) | Difference with UTCs |

|---|

| A-Level Mathematics | 126 | 11.2 | +2.4 |

| Principal Learning Engineering (Diploma) | 103 | 9.2 | +9.2 |

| A-Level Physics | 98 | 8.7 | +5.1 |

| BTEC Engineering (Extended Diploma) | 64 | 5.7 | +5.6 |

| BTEC Computer Appreciation (Subsidiary Diploma) | 50 | 4.5 | +3.5 |

| BTEC Engineering Studies (Diploma) | 45 | 4.0 | +4.0 |

| BTEC Computer Appreciation (Extended Diploma) | 44 | 3.9 | +3.8 |

| A-Level Chemistry | 40 | 3.6 | -1.6 |

| BTEC Engineering Studies (Subsidiary Diploma) | 38 | 3.4 | +3.3 |

| A-Level Biology | 35 | 3.1 | -2.9 |

Making the grade

That's all well and good (at least to a science nerd like me), but how do UTC students do at these subjects? Regular readers of this blog will be aware that in looking at attainment it's unwise to simply compare one group of schools with all others (as we have admittedly done above for subject choice). This is because UTCs are likely to be different from the average school in a variety of respects, and any differences in outcomes might not be due to factors other than the specific ones that make them UTCs. Figure 1 shows that this is indeed the case.

Figure 1: Pupil characteristics (2015)

On average, UTCs (red column) have much higher proportions of boys than other mainstream state secondary schools (dark blue column). They also have lower proportions of students for whom English is an additional language (EAL) and slightly fewer who are eligible for free school meals (FSM; a measure of poverty). Although not shown in the figure, they also tend to have shown marginally lower performance at primary school: their mean Key Stage 2 point score is 27.1 versus 27.6 for non-UTC schools.

To control for this, we created a group of 'Similar non-UTC schools' (light blue column) by matching each UTC to five non-UTC schools that are in other respects as similar as possible. As well as controlling for the measures above, we also took into account academic selection (in effect, grammar schools were excluded) and whether or not a school is in London (which shows many different educational attributes to the rest of the country). The resulting group of similar non-UTC schools is a much closer (though still not perfect) match to the UTCs in terms of proportions of boys, EAL students and FSM students. Their prior attainment figures also corresponded more closely, with a mean Key Stage 2 point score of 27.2.

With that, we can look at the academic performance of these three groups. Figures for 2015 are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: GCSE attainment (2015)

Again, these data are from 2015 GCSEs, so only 13 UTCs are represented. It's nevertheless clear that they underperformed other schools on every common GCSE metric – 'five A*-C grades' (a commonly used threshold measure), average point score (which takes better account of the grades students achieve in each subject) and value-added (which allows for each students' prior attainment at primary school). Importantly, although the group of similar non-UTC schools also do slightly worse than the average for all non-UTC schools (to be expected since UTCs contain a lot of boys and they tend to underperform girls), the differences are slight. Most of the differences between UTCs and the rest are therefore not explained by these factors.

Last week the Department for Education also released preliminary results for 2016 GCSEs. As well as the usual 'five A*-C grades' measure, these featured two new metrics, Attainment 8, which is similar the average point score we looked at above, and Progress 8, which is akin to the previous value-added metric (see our previous post on this topic). Because they are more recent, these results provide information on a larger number of UTCs: 25 in all, though as noted above the data are still provisional. The results are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: GCSE attainment (2016 provisional results)

The conclusions are very similar: whether we look at the 'five good GCSEs' measure, Attainment 8 and Progress 8, UTCs underperform not only other secondary schools but also the subset of secondary schools that are in other ways very similar to them.

A-Levels and similar qualifications seem to show a very similar picture, at least in 2015 (the most recent year for which those data are available), even when vocational as well as academic qualifications are included. However, this analysis is inevitably made more complicated by the fact that BTECs and other alternatives to A-Levels feature so heavily at UTC sixth forms. In addition, the sample sizes are smaller than for GCSEs, so specific numbers won't be presented here. It's also worth mentioning that our preliminary analysis of Studio Schools came up with somewhat similar results, though so far they seem to be doing worse than UTCs at GCSE while doing better at sixth form.

Now, what's the question?

What to make of all this? UTCs do indeed seem to promote scientific and technical subjects – or at least attract students who already have a penchant for them. But attainment so far has been unimpressive, even after controlling for potentially confounding factors such as gender balance.

There are certainly reasons not to consider this a huge problem. For one thing, UTCs are still very new. Many have yet to report any exam results and those that have are still just getting going. Perhaps even more significantly, if they promote scientific and technical subjects – reckoned by some to be more demanding than the average humanities subject – then we might expect them to pay a penalty in terms of raw exam performance and should therefore not judge them too harshly in this light. With their intake at the unusual age of 14, it's also possible that UTCs accept a disproportionate number of students who, despite previous good performance at primary school, have not progressed well in the early years of secondary school. Indeed, Nicky Morgan has suggested that UTCs should start accepting pupil at the age of 11, which would bring them into line with most other state secondary schools, but perhaps also make their vocational bent harder to sustain.

Whether or not UTCs are the answer, then, depends on what the question is. If their aims are largely vocational then the ultimate test will come when we see where their students end up after graduating. The data on that front are still sparse so we will have to wait a bit longer before being able to answer that important question.

Now with added Progress 8!

22nd October 2016 by Timo Hannay [link]

This week the Department for Education (DfE) released the first nationwide school-level data set for its much anticipated1 Attainment 8 and Progress 8 measures of secondary school performance. (See this PDF document from the DfE for more details.) These are intended to replace the old "five A*-C GCSEs" measure, which has been widely used, including in the DfE's own exam league tables, but has at least two major shortcomings:

- It's a threshold measure, which means that each pupil either gets five good GCSEs or they don't – there's no information about the degree of over or underperformance relative to this standard. Not only does this make the measure incomplete, it also creates perverse incentives to focus effort on children who are close the threshold while ignoring the rest. Attainment 8 overcomes this by looking at a broader range of subjects and, most importantly, by using a continuous scoring system that takes into account each pupil's grade in every relevant subject.

- It only measures absolute attainment. This depends not only on how well each pupil does while at secondary school, but also on their ability when they joined from primary school. Academic attainment is certainly important in creating life chances, but progress is a fairer basis on which to judge the performance of schools. The DfE has previously provided various "value-added" measures, so the ideas behind Progress 8 are not entirely new, but it will hopefully provide a new level of prominence and consistency to this approach.

Plus ça change?

These are therefore understandable changes, but how much difference do they make in practice? We can't do proper justice to such a broad question in this short blog post, but it's still interesting to take a quick look and get an initial sense of what the new data say, particularly by geography.

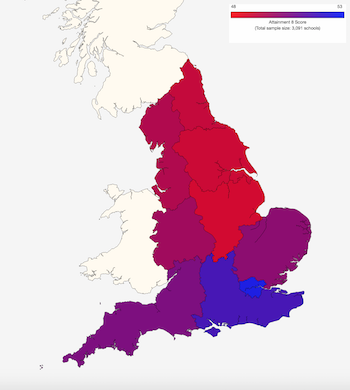

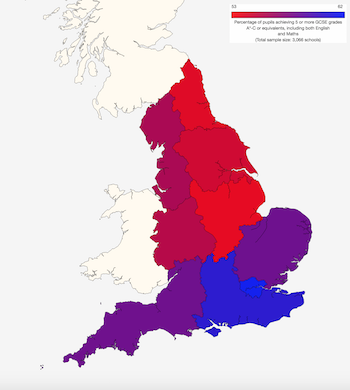

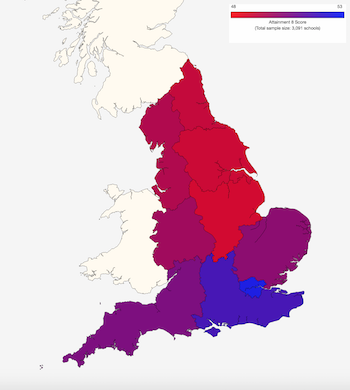

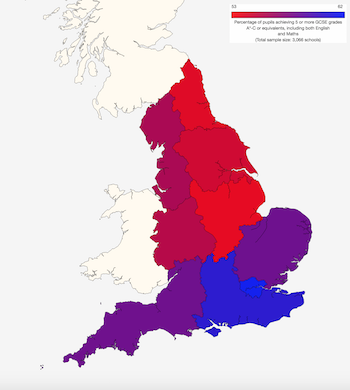

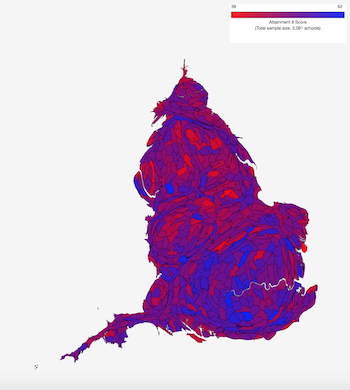

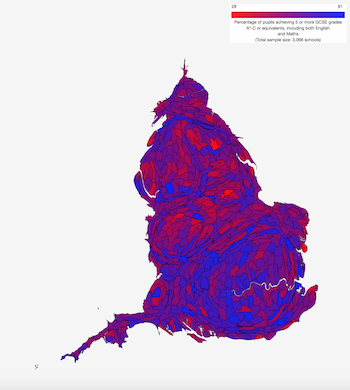

Maps 1 and 2 show, respectively, the average regional values for this year's Attainment 8 scores and the corresponding values for the "five good GCSEs measure" last year. At this level the differences are very small indeed – and we continue to see the stark north-south divide that we wrote about last year.

Maps 1 and 2: Average Attainment 8 score (2016) and percentage of pupils gaining five good GCSEs (2015) by region

(Click on any of the maps in this post to go to larger interactive versions.)

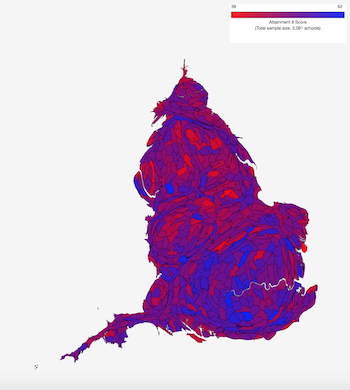

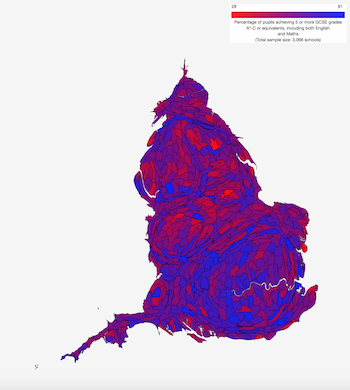

More or less the same is true even at the much finer-grained level of Westminster parliamentary constituencies, shown in Maps 3 and 4. For these, we've used 'cartograms' in which each area is resized according to the number of pupils attending school there; this makes small but densely populated urban areas easier to see. Bear in mind that we're looking at two different years, so would expect to see some changes even if we were using exactly the same measure. Given that, the differences still look modest.

Maps 3 and 4: Average Attainment 8 score (2016) and percentage of pupils gaining five good GCSEs (2015) by parliamentary constituency

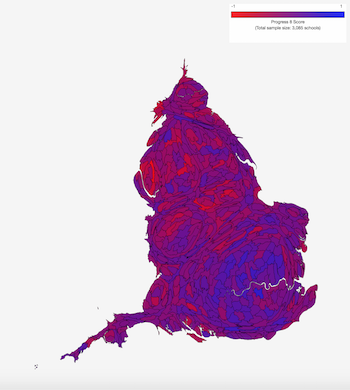

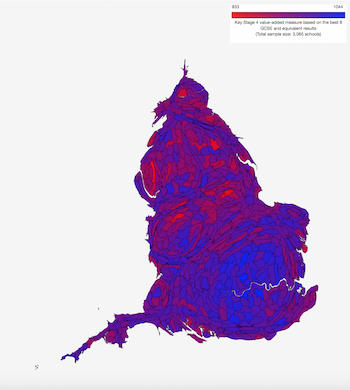

Welcome progress

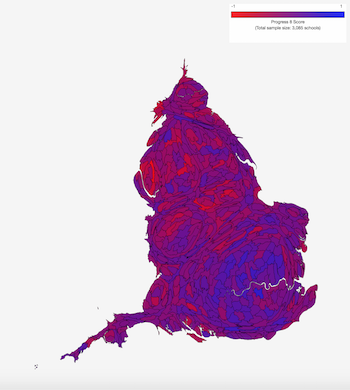

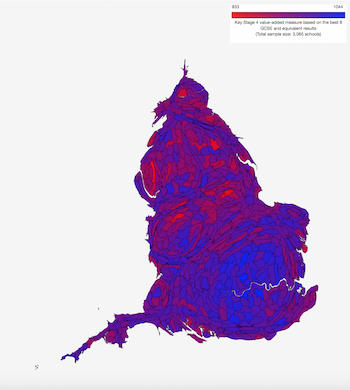

What about Progress 8? Maps 5 and 6 compare this with the DfE's previous GCSE "value-added" metric. That used each pupil's best eight subjects regardless of what they were. Progress 8 gives priority to certain traditional academic subjects that the DfE have deemed important and gives double weightings to English and Maths. These create more noticeable differences than we saw with attainment. In particular, there's a less clear distinction between high-performing areas – most notably London – and those with poorer results, though there's still a visible north-south divide.

Maps 5 and 6: Average Progress 8 score (2016) and GCSE value-added score (2015) by parliamentary constituency

Here at SchoolDash, we welcome these new measures as more appropriate ways of judging pupil and school performance than the cruder ones that have been popular in the past. In a way, the fact that the new metrics show broadly similar results to the old ones, at least at a national level, serves to reassure us that both of them are measuring real underlying patterns that aren't too sensitive to our choice of statistical method.

If these really are more discerning measures (which I think they are) then the main effects are probably to be seen at the level of individual schools. A proper analysis of those will need to wait for another time, but until then go to SchoolDash Explorer, where the secondary school indicators for attainment and progress now incorporate the 2016 Attainment 8 and Progress 8 data. You can use it to explore these statistics for the localities and schools that interest you. And as usual, do send us any feedback.

Footnotes: