Have GCSE grades really returned to normal?

24th November 2023 by Timo Hannay [link]

Update 24th November 2023: See also this coverage in Schools Week.

Conventional wisdom has it that, following three years of COVID-generated disruption, school exams in England have finally returned to pre-pandemic norms. In many important ways this is perfectly true: traditional written exams are back, so the system no longer has to rely on centre- or teacher-assessed grades. And although some special support has remained in place for pupils affected by COVID, the grade inflation seen in 2020-2022 has gone and grade distributions look much like they did before COVID struck.

Or do they? As pointed out by Duncan Baldwin in an opinion piece in Schools Week, there have been early signs that more pupils than usual are getting no grades at all in key subjects. This can be for a variety of reasons, from performing badly in the exam to not turning up or not being entered at all. Here we use the recently released 2023 GCSE results data to investigate this issue further.

Inflation target

Figure 1 shows the distributions of GCSE grades for 2019 (the last pre-pandemic year), 2022 (the next year for which school-level data are available) and 2023 (the current, supposedly back-to-normal year). In both Mathematics and English Language, we can see that high grades (in purple and blue) grew as a proportion in 2022 before falling back again in 2023 to more or less the same as levels as in 2019. Lower grades (in yellow and green) did the opposite, shrinking in 2022 before rising back to pre-pandemic levels in 2023.

But take a closer look at the very bottom of the graph, where the grey, and red layers indicate pupils who didn't obtain a grade at all and you'll see a different trend. For these, recent years have shown only increases, with no return yet to pre-pandemic norms.

(Use the menu to switch between English and maths. Click on the figure legend to turn individual grades on or off; double-click to show one grade on its own. Hover over the graph to see corresponding values.)

Figure 1: Proportions of pupils by GCSE grade

This can be seen more clearly in Figure 2, which shows the same data, but concentrates on these lower bands.

Let's look first at English. 'No entry' (dark grey) indicates pupils who have not been entered for the exam at all (calculated as the difference between the cohort size and the total number of entries). This proportion, though low, has been on the rise. The same goes for 'No result' pupils (dark red), who were entered for an exam but for some reason didn't complete it and for 'Grade U' pupils (light red), who sat the exam but performed too poorly to receive a grade.

Other categories came and went. 'No data' (light grey) indicates pupils who were entered for the exam but did not appear in the grading data (the difference between the reported number of entries and the total number of graded results). These spiked in 2022 but have since returned to negligible levels. The same goes for the smaller category of 'Covid impacted' pupils (orange).

The overall effect is that pupils receiving no grade at all in English Language have roughly doubled between 2019 and 2023. The effect for maths is similar if less extreme.

(Use the menu to switch between English and maths. Click on the figure legend to turn individual grades on or off; double-click to show one grade on its own. Hover over the graph to see corresponding values.)

Figure 2: Proportions of pupils not obtaining a GCSE grade

Spotty picture

Whenever an education trend like this comes to light, it's usually worth asking whether the effect is felt equally across all types of school and every part of the country. Spoiler alert: the answer is almost invariably no.

Figure 3 compares the proportions of pupils receiving no grade in 2019 (horizontal axis) with those in 2023 (vertical axis). Dots represent different types of school and are scaled based on their respective cohort sizes. Note that most of these lie above the diagonal because the proportions of pupils receiving no grade mostly grew between 2019 and 2023.

For English across all schools (grey dot), it increased from 1.7% to 3.3%, as we have already seen. But when we group schools by their Ofsted ratings there is huge divergence, with low-rated schools showing both much higher proportions and much bigger increases. There are similar, if less extreme, patterns when we look at in-school disadvantage or local deprivation. There are also notable trends by school size, academy status and trust size, though regional variations are relatively modest by comparison.

For maths the change across all schools was of course smaller, but variations by Ofsted rating were even more extreme. Patterns by in-school disadvantage, local deprivation, school size, academy status, trust size and region were broadly similar to those for English. (Click here to see all groups again.)

(Use the menu to switch between English and maths. Click on the figure legend to turn individual groups of schools on or off; double-click to show one group on its own. Hover over the graph to see corresponding values.)

Figure 3: Proportions of pupils not obtaining a GCSE grade by school type

This matters, of course, because it means that thousands more children than usual, many of them already facing disadvantage, are finishing Kay Stage 4 without obtaining English or maths (or potentially other) GCSE grades. But as Duncan Baldwin points out, it also has an impact on school assessment because such outliers can have disproportionate effects on Progress 8 scores.

Insofar as these trends are genuine reflections of school failures then fair enough. But where they reflect post-COVID circumstances beyond the school's control – note for example the persistently high pupil absence rates, which are also not evenly distributed – we might be doing them a disservice.

We welcome your comments and suggestions: [email protected]

An unconventional convention

21st November 2023 by Timo Hannay [link]

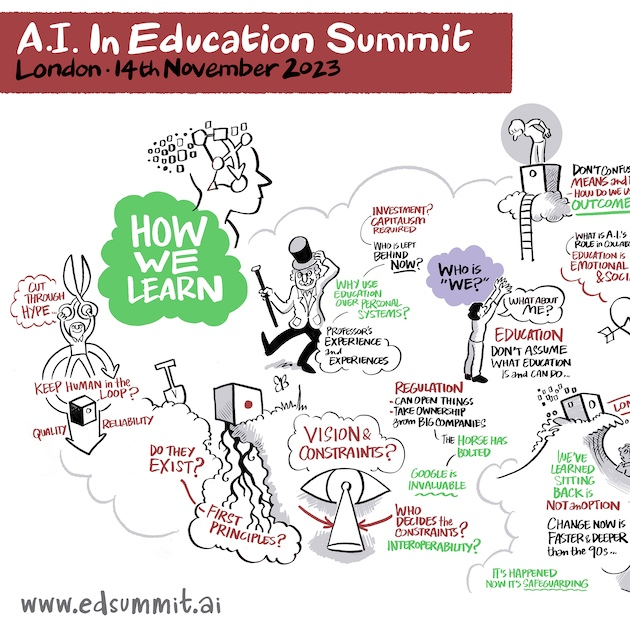

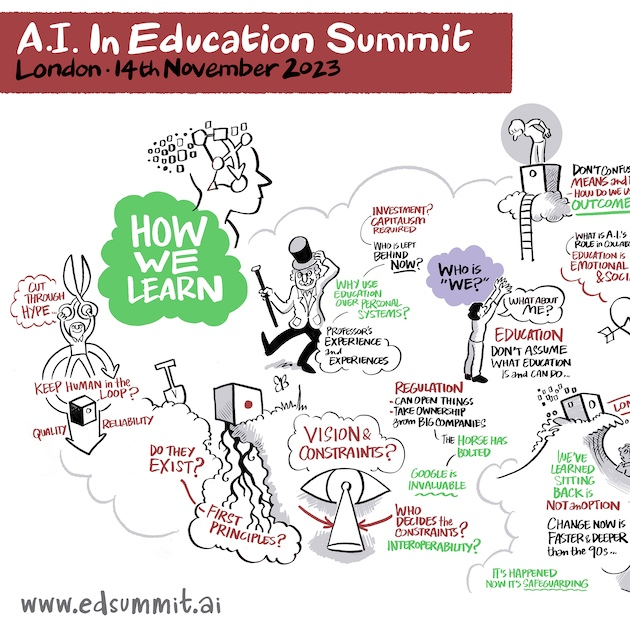

Last week, SchoolDash was privileged to be involved in convening an AI in Education Summit as part of the AI Fringe, inspired by the UK government's global AI Safety Summit at the beginning of the month.

Our event included about 80 participants from across government, technology, business, the charitable sector and (of course) education. Discussions were largely freeform and conducted under the Chatham House Rule, so we can't say who was there, but a visual summary together with AI-generated highlights are available on the event website: https://www.edsummit.ai/.

As always, we welcome questions and comments – please write to us at [email protected]. Please also consider signing up for our free monthly-ish newsletter.